Led by a whale

In this newsletter, we invite you to explore the notion of the body through presence, movement, and improvisation, which can be experienced through any activity and at any time of the day.

Hello, wonderful SoC community!

We hope you are e feeling refreshed, rested, and relaxed!

First off, just a little note to let you know that the next SoC Alumn* meeting will take place on Thu 26 Sept, 5-6 CET. Please mark your calendars and join us! 📆 🤸🏻♂️🪁💫

Now, as promised, a deeper dive into the healing, contemplative, and inspiring worlds of SoC Alumni has arrived (Kit, thanks for starting this off last year!)

For this year’s long read, we are featuring a conversation with Lina Zeller. It is dedicated to the awareness of the body. For the past twenty years, Lina has worked as a movement artist, Pilates instructor, and dance teacher.

But first, let’s have a quick warm-up for our minds and bodies

Here’s a quick poetry moment (click click) to appreciate our bodies.

Led by a whale

In line with our promise to provide a space to share your invaluable knowledge, skills, and ideas creatively, we have collaborated with Studio106LA to present our second show. This time, we are showcasing Lina Zeller’s work, an excellent addition to the interview below.

Now, let's dive into the heart of this newsletter and enjoy the conversation with Lina.

L: I'd like to delve into the intersection of the body and mind within your project's framework, particularly in relation to the concept of commons. How do you see the body as both a shared experience and a deeply individual journey, especially considering diverse abilities and cultural backgrounds?

Lina: Yes, interesting question! I'm fascinated by movement. It's something that really captivates me. I've been drawn to it since I was young.

Later I began studying it formally. When I was eight, I started attending dance classes regularly, eventually dancing professionally for about 20 years. The human body and its movements are endlessly intriguing to me, particularly how we interpret our surroundings through movement.

For instance, when I'm on vacation at the beach, I find myself spending a considerable amount of time observing people's walking patterns. Whether I'm at a café or by the shore, I'm absorbed by the nuances of human motion. If someone gestures with their left hand, it catches my attention immediately. It's like discovering a new aspect of movement behavior.

Similarly, I'm fascinated by the little habits we inherit or adopt. For example, noticing that I wake up and get out of bed exactly in the same way my mother does is a revelation. It's interesting to notice how we absorb the gestures of other people around us. These small details never fail to fascinate me.

And yeah, also movement and stillness—how it feels to move as little as possible, for example. I recall being part of a research project where, for 24 hours, we aimed to minimize both movement and noise to the greatest extent possible. For instance, opening a cupboard had to be done as quietly as possible, and even handling pots and utensils had to be mindful of the sound our bodies produced. Voice was also included, so we had to speak as sparingly as we could within that timeframe. These experiences always intrigue me.

In my dance career, especially in my youth, I was primarily focused on developing technical abilities. However, it's fascinating how my perspective has shifted over the years.

Technique has taken a backseat, and I've become more attuned to other aspects that heighten awareness beyond mere technical skills.

And that's what I wanted to bring to the School of Commons. It's this blend of experiences from my upbringing. I was born under the equator in South America, and I grew up during a time of dictatorship until I was nine years old. Despite the challenging political climate, I have vivid memories of my parents dancing in the kitchen. Coming from a culture rich in dance, I decided to infuse this aspect into the School of Commons. How could I bring movement/choreographical elements to relate or influence my peers?

When I considered the diverse backgrounds of the individuals involved—activists, artists, researchers, scientists—I realized that despite our differences, we all share bodies. This commonality inspired me to create an environment focused on movement and play. I wanted to cultivate a sense of playfulness, similar to how children effortlessly move and explore their surroundings. I aimed to reintroduce this sense of uninhibited movement, but in an adult context where we can embrace fun and playful interactions. So, essentially, that's what I set out to achieve.

And this aspect of the body and its relationship to space—how do we connect with the space we inhabit?

How do we observe not only other bodies but also the details within our environment?Can we notice the smallest red object in the room or the largest yellow one? Are we attuned to the dust on the floor or the intricate patterns of the wood? These elements contribute to our awareness, extending beyond mere visual observation to include aspects like breathing, rhythm, and movement.

Cultivating this heightened awareness is essential. It's about being present in our bodies, acknowledging movement while also embracing stillness. This interplay between motion and tranquility intrigues me the most, which is why I chose to incorporate it into the practical workshop at the School of Commons.

L: In describing the School of Commons project, you mentioned using tools such as letters to facilitate conversations about movement, offering a means of personal communication. So, in essence, the translation of your intent to unite people through movement also involves communication on a deeply personal level. I ponder whether those who haven't experienced the vibrant expression of movement in their culture can still connect with it. Is it something inherent in all of us, waiting to be rediscovered, regardless of our cultural context? It's an intriguing question that delves into the universality of human movement and expression.

Lina: Yeah, well, we are all embodied, and we all possess a sense of movement and rhythm, so it's about tapping into that and inspiring people to engage in play. I chose handwritten letters as a means of communication because I'm also deeply fascinated by them. Throughout my life, I've both written and received a number of handwritten letters, and I've found them to be a powerful way to connect with others. Before writing to someone in the School of Commons, I would spend about a week immersing myself in their work, reading all their texts, essentially delving into their world. Then, I would craft the letter based on what I learned, creating a structure that would guide the recipient through a choreographic experience.

I use the term "choreography" here not in its traditional sense but rather to signify the incorporation of choreographic elements into the handwritten letter. The goal was to prompt the recipient to move through the letter and engage with its contents physically.

The letters bridge reading and moving, creating a tangible connection between two universal experiences. They serve as visual representations of movement and interconnectedness, offering a framework for individuals to engage with movement concepts. These letters aim to uncover broader perspectives and personal insights. They invite individuals to explore movement, not just as a physical act but as a reflection of their own interests, personality, and worldview.

L: That choreographic kit you mentioned, created by Professor Gabriele Klein in Germany, sounds like an invaluable resource.

Lina: Her research, alongside two other European researchers, Gitta Barthel and Esther Wagner, sought to explore the diverse approaches choreographers take in their creative processes. By cataloging and organizing these methods, they aimed to understand how choreographers structure movements and build choreographic compositions. This kit, meticulously organized with booklets, served as the foundation for my letter-writing process and choreographic collaborations.

Inspired by this, I experimented with writing with closed eyes or varying speeds, mirroring the sequence of dance classes where movements are performed on both sides of the body. I even attempted writing with my non-dominant hand, akin to mirroring movements in dance. My goal was not only to infuse my letters with elements of dance but also to prompt the recipient to engage in the movement themselves. By incorporating these ideas, I aimed to create a sense of kinesthetic empathy, where the reader could experience and respond to movement through the act of reading.

Lena: Yeah, interesting. When you say that you were writing with your left hand, are you right-handed?

Lina: Yes. And yes, absolutely, you've touched on a crucial aspect of accommodating diverse abilities and limitations within movement practices. By challenging our own abilities through unconventional exercises like writing with closed eyes, we not only test our limits but also become more attuned to our embodied experiences, regardless of our individual capacities.

In the context of the School of Commons or similar initiatives, where participants come from various backgrounds and abilities, it's essential to create inclusive and adaptable practices. This involves recognizing and respecting the diverse needs and limitations of individuals, whether they stem from injuries, differing abilities, or simply varying levels of experience in movement.

Your mention of Feldenkrais resonates deeply. The Feldenkrais Method emphasizes subtle, incremental movements to enhance body awareness and efficiency. Incorporating elements of this approach can indeed provide valuable insights into how small adjustments can profoundly impact our bodies.

In designing movement sessions or workshops, it's vital to offer options and modifications that cater to individuals with different needs. This might include providing variations of movements, offering props or support for stability, or allowing for rest periods during sessions. By fostering an environment that values and accommodates diverse abilities, we can ensure that everyone feels empowered to explore movement in a way that suits them best.

It's evident that creating an inclusive environment where different needs are accommodated was a priority in the movement sessions. The decision to refrain from speaking during the sessions allowed participants to fully immerse themselves in the experience without the distraction of verbal communication. By removing this common mode of interaction, individuals were encouraged to engage more deeply with their bodies, space, and movement, fostering a heightened sense of awareness.

I appreciate the perspective that there's no inherent right or wrong way to move, emphasizing that the only rule was to refrain from speaking. This open approach allowed participants to explore movement without feeling constrained by preconceived notions of correctness. Each individual was free to navigate their own challenges and limitations, finding creative solutions that suited their unique abilities.

Observing how people with diverse abilities approach movement challenges highlights the innate creativity and adaptability of the human body. Regardless of technical proficiency or prior training, everyone was able to find their own way of moving within the given framework. This underscores the idea that the body itself suggests what's needed, guiding individuals to listen and respond to their own limitations and possibilities.

L: It sounds like the focus of your movement sessions at SoC was not on achieving a specific outcome or correctness but rather on the collective experience of moving together. One exercise you introduced, where participants form a circle and take turns moving into the center without any designated leader or follower, seems to exemplify this approach.

Lina: It emphasizes the idea of the group functioning as a cohesive organism, with movements emerging from the collective rather than from individual initiative. This approach fosters a sense of unity and interconnectedness among participants, as everyone contributes to the group's movement dynamics. By relinquishing the need for individual control or direction, participants are encouraged to attune themselves to the group as a whole, sensing and responding to each other's movements in real-time. It's clear from some feedback that these sessions were not only enjoyable but also deeply challenging and fulfilling.

L: Yeah, it's intriguing because, in a way, body language is a language, and we are used to verbal language as the one that allows us to connect. Well, actually, verbal language isn't sufficient because we also read people's body language, and that helps establish trust and certain communications, letting boundaries be there for us.

Lina: This is very clear. You know, I was thinking the other day, okay, I'd like to go back to the gym, but then I thought, at the gym, it's all about repeating a controlled movement. Do I want that? Do I want repetition? No, I don't. So what am I going to do? Twice a week, I lock myself in a room here at home, blast loud rock and roll music, and dance with my eyes closed for an hour. That's my fitness routine. It's so much fun because I sing along, totally off-key, and I dance, sometimes even out of rhythm and clumsy, but I have a blast. This is my aerobics. It's a way for me to experiment with movement in ways I wouldn't if I were being observed. I'd never dance this way at a party or with students or colleagues. It's the freedom to go beyond, to experiment with movement without any constraints.

And this experimentation is something I think I bring into the letters, and I also want to bring into the movement sessions that I did in the School of Commons. It's about going beyond. Now, let's rethink certain movement dogmas for a dancer or for an office worker. How can we go beyond, with respect but also with awareness? It's about creating a space where people feel comfortable locking themselves in and just dancing for two hours.

L: Yeah, it's also, I think, what you said, that you're not observed, you're on your own, so you're within the safe space of your own privacy. I wonder how, for many people, it's probably very difficult to move while being observed or to break that boundary before starting to move in a group, and perhaps even improvise in a way they've never done. So this connection between audience, participants, and viewers, even those who aren't specifically an audience for the performers or the session, how do you see those connections? Can they intertwine, or are they entirely separate? Can they influence one another?

Lina: Yeah, this is something very interesting. When I was teaching back at university, we experimented with how dancing changes when done with closed eyes in a room where nobody can see us, compared to dancing in the middle of a room with everyone in a circle observing. It's related to the letters too. Writing in my diary, where I know I'm the only reader, is different from writing a letter. What from my diary, from this unobserved space, comes into the letter? But the letter is being sent to someone, so there's a frame.

The idea of “Beauty” can be a trap, sometimes, whether in movements or when we try to be poetic while writing. I often get trapped in the desire to write beautifully. To escape this trap, I started writing letters. I wanted them to be poetic, but then I got trapped again. It's easy to lose yourself when you start composing and interpreting from a third perspective, almost like viewing yourself from the outside. You're not alone anymore in this.

One thing that really helped me was when I started allowing the writing mistakes and misspellings to be shown, refusing to erase them. Instead of starting a new page with no mistakes, I would really risk it and keep going on top. I started allowing it, and it's really interesting. I wrote three letters, each around 11 pages, and each one took around five weeks to be ready. In the very first letter, the handwriting is very neat, the paper pristine, but by the end, it's totally mixed. I got out of the trap of making a beautiful work into making a real work. So the mistakes became part of it, and the uncertainty and the doubts. I think doubts enrich any research.

L: What is your favorite ways and workings?

The ways and workings, the one I have for my project is letter writing, and I found some others that are very interesting for me, which is connecting writing with graphic elements. I've also discovered other fascinating methods, such as integrating writing with graphic elements. Why is this connection important? Does it prompt a different mode of thinking? Yes, indeed. For instance, one idea within this choreographic game entails filming oneself discussing research inaccurately, then analyzing the resulting "musicality" of the speech and translating it into a graphic or drawing. This process reorganizes movement into visual representations. Another approach involves using the letters as a form of game, fostering a return to a childlike state of freedom. This allows us to break free, and it is definitely fun.

L: It also has structure, right? So, every game has sort of a structure while it still allows for things like curiosity and engagement.

Lina: Yes, exactly. Games offer precise frames, they are the rules. So these frames that I offer in the letter or that I offer in a movement class, surrounds us with inputs. We get inputs for movement from these “rules” or frames. To write the letters, I also got a lot of input, influences, and references from other artists and writers. For example, there is this artist I like very much, David Jesus do Nascimento, and I get very fascinated by how he works with family histories, with ancestry and myths and how he relates to the river nearby where he grew up. He says he “works collecting affections from the riverside ancestry,” and I love this definition of his own work. He comes from a simple family that lives in front of this huge amount of water, and all his work is very much related to his environment and to how he relates his body to this specific place, to the trees and fishes, myths, memories, and family pictures. Besides his pictures or watercolor paintings, his writings are also fantastic: He writes in a way that really goes beyond grammar structures: , he makes his own grammar possibilities, and I brought that somehow to the letters I wrote. It's really very nourishing to read/see him/his work and enjoy the way he goes beyond and stretches out images, stories, or grammatical rules.

L: Yeah, really. Like as we said, changing the rules, creating your own, and having the right to be as you wish to be in the world outside of the constraints of society is the same way that we are constrained in the body, thinking we cannot move a certain way. Oh, and don’t forget to mention your recommendations to the readers <3

Lina: Exactly, it's like we're confined by certain rules. For instance, I can't move freely in every space. There are specific movements expected in different environments. In a bank, I can't behave as I would at the gym. Similarly, there are societal norms dictating how we move in various settings, like sitting in a chair in a university. Even in public spaces, like the street, there are unspoken rules governing our movements. It's fascinating how these social norms evolve over time, shaping our behavior and interactions. And it changes with time. For instance, 500 years ago, we had absolutely different social rules. And the body inherently exists within this framing of rules.

I often think about David Jesus do Nascimento; his work feels very dreamlike, reminiscent of the world of dreams. The way he writes and talks about his past, family, and nature seems to transport one to dreamlands. Last year, I experienced something similar during a Watsu session, akin to shiatsu in water. Floating in warm water with closed eyes while someone guided me, I felt a sense of surrender as my body moved without my control. Memories from childhood surfaced, blending with sensations and moments of falling asleep. These experiences, unique to a different perspective, echo the impressions I get from Nascimento's work.

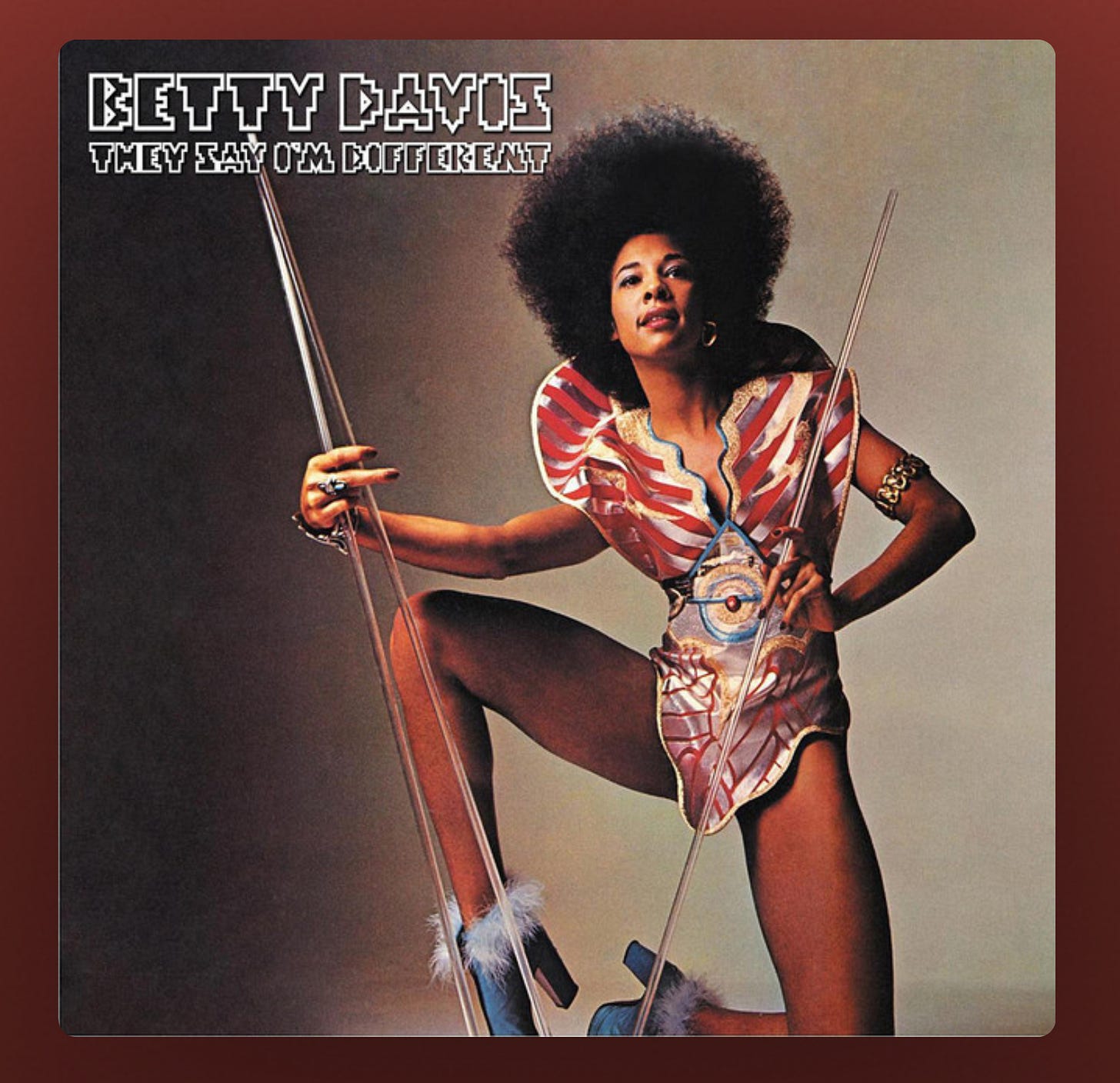

On another note, I'm captivated by Betty Davis's music. I only recently discovered that she was Miles Davis's wife. Her powerful, sensual presence is palpable, especially in the covers of her albums. She exudes a raw, untamed energy that goes beyond mere beauty, setting her apart from other pop singers. It's a recent discovery for me, and I find it enriching to share and exchange references like this, as it broadens our perspectives. In her work, I clearly see how the connection between voice and movement can be profound, reflecting how one's voice can be mirrored in their body language.

Lina: I recommend the book "Correspondences" by Tim Ingold, a British anthropologist who writes poetically about matter, the world, lines, words, and the importance of handwriting. This book really resonated with me, especially before writing letters, as Ingold passionately advocates for hand-writing. He beautifully explains why writing letters is so important and how it differs from emails or other forms of communication. Handwriting is a corporeal action with its own timing; it makes you think before you write, and the ability to add layers and revisions adds to its beauty.

When I think about places that have left an impression, Zurich, where I now live, stands out. What truly brings back sensations, memories, and stories for me in Zurich are the handmade chocolate shops. It's like a spiritual experience—each piece of chocolate feels heavenly. It's expensive, so I indulge sparingly, but the way it melts and its texture make every bite a treat. It's a great Swiss recommendation!

Explore Lina’s show here and let us know if you’d like to collaborate with us at Studio106LA.

Staying in touch,

Lena (and SoC Alumn*)