An Aural-Centered Space of Collaboration

Alumn Updates

Hello, dear friends of the School of Commons!

In this issue of the alumn updates, you can get to know two ongoing SoC alumn projects about sound, from Elisa (SoC ‘22) and Pule (SoC ‘21, ‘22, ‘23). What follows are highlighted excerpts from our lovely conversations about peer learning; trust and vulnerability; decentralization and de-centering; virtual spaces and accessibility; and, of course, sound and music. These alumn updates will continue to highlight the ongoing work of SoC alumns - so if you’re interested in featuring your work, please get in touch for more information (more details at the end of this post).

Before jumping into these reflections on learning through & with & around & within sound, you can also revisit this interactive web-based sound playground from the Noisy Playtime Warmup in the SoC “Ways & Workings”. As a result of our recent town hall discussion, this newsletter’s goals is not only to highlight ongoing work, but also to re-encounter past work within the SoC, including “Ways & Workings” posts, relevant to the theme of each letter.

Elisa Lemma is a classically-trained musician and former (‘22) School of Commons fellow whose project involved hosting Listening sessions, including with other SoC fellows. In these sessions, Elisa played classical pieces on her piano, and held space for conversation around that piece. These conversations specifically welcomed people without classical musical training to participate in speaking about their experience of each piece:

“In the beginning, I tried to choose pieces where I could guide the audience through, from a structural point of view. Classical music has always been very structured: there's the teacher who knows how to play this, and you learn from the teacher how to do it. You're allowed to experiment, but within a context in which there is still a wrong and a right. When I started, I wanted to get out of this, because I had suffered in my own experience. But I still thought that I have to give them guidance and the tools that I had, because I process music through these tools. At the beginning, I thought that it was absolutely necessary that they knew how the piece was structured, that they knew what the theme was, and so on. Then I discovered that it's not at all like that; I saw that the conversation was really flowing, the people were all really comfortable, talking for two hours. It was super easy and super fun, and I started to trust them, but also I started to trust myself more, seeing that I didn't have the monopoly on what we're hearing or how we should hear. It was suddenly something shared.” -Elisa

Elisa and I start our conversation by imagining it as a virtual studio visit, with Elisa in her home in Milan, and me visiting from my temporary home in Tainan.

Elisa: Here is a piano-

Kit: Hi piano!

Elisa: -with a plant playing it right now!

Kit: What is the plant playing?

Elisa: The plant is playing Chopin, which I've been working on the last month, which is a piece, which is super beautiful. It’s called Barcarolle, it's inspired by Venice and has a very aquatic way of making sounds. I was thinking of using it for the next round of Listenings. Before, I wasn't feeling enough confidence, but now I really see that maybe other artists coming from dance, theater, and so on can find it an interesting learning process. It creates this kind of common knowledge, and we try to represent it through words. The experience isn’t the same for everybody, but as soon as you start talking about it, you start influencing each other's experiences, so they start to merge, and maybe you change ideas, maybe you don't; but it’s not like that you should come up with a definite way to describe the piece. It's about classical music, but it's also about attention and concentration on something that is abstract, but we all share it. It's in the room, but we don't see it. It develops in time, but we don't see it.

Yesterday evening, I worked for this event of the Filarmonica della Scala. They organize this concert in the dome square, which is supposed to be music for everybody, because it's a free concert. It is always really nice. But in the middle of the square, you have the VIPs and institutional guests seated in a fenced area, and then you have all the rest standing outside. This happens every year, it's not something that's considered weird, and it isn't something that anybody complains about. But whenever classical music says, “Okay, this is a free concert,” then you have to put a special place for special people in the middle. Within this kind of context, you have a system of power and a system of prestige that needs to be maintained. The moment I say, “I'm a trained classical musician, and I don't know more about classical music than you. Your vision can really be as good as mine,” this really just doesn't have a place in this context. The crucial thing of my project is, what are we doing this for? What are we playing this for? Why are we playing it like this? I've studied classical music for many years in a context in which it didn’t make sense for me. Now, I have the time and space to see if I can create something where it makes sense for me.

Kit: Aside from in-person Listenings, you’ve mentioned before that you tried remote video calls.

Elisa: I've also tried to have Listenings through zoom, and it really doesn't work. But I see the potential of having only an anonymous audience, without names, without everything like that. That also could make people freer to interact, because nobody knows who you are. So you can also open up a possibility for having an active audience that speaks and a passive audience, which just listens to see what the others are saying, and maybe comments once in a while, but doesn’t have to. I've always had groups where everybody at one point was participating. But I always think that enabling passive participation could also make it more accessible.

Kit: I’m curious to hear more about exploring a space of this kind of mutual vulnerability online or in a physical space, anything you think might be cool to experiment with?

Elisa: It would also be interesting to have a kind of regularity, like one session a week. I would love to have like other musicians, also in the session. If there is a kind of group of people who are interested and they know that weekly, they can participate in the session, either talking or not talking. If they like, they could suggest pieces to listen to together. In other words, creating an environment in which there is enough energy and enough people so that I'm not the center of it anymore. I had asked a lot in terms of concentration and vulnerability, and everybody, I think, was happy with it. But still, it's not something that you want to do every week; but if you have a group where everybody participates that would make it easier for everybody and could create a system in which if a new person comes in, there's already a thing going on.

Themes of de-centering and decentralizing, as well as repetition and sustained interaction came up in my conversation with Pule, too, as they describe their project “not just an art installation or a single event, but a space of continuous sustainable collaboration.” Pule kaJanolintji is a scholar of linguistics and a cultural historian of speech practices of Azania/!Naremâb, promoting writing systems of the continent, like N'Ko or Ditema tsa Dinoko script. Their MA research describes South African cryptolects - secret forms of speech. They are both a former (‘21, ‘22) and a current (‘23) School of Commons fellow, and we talk about their ongoing work to create a peer learning environment in southern Africa.

Ubumina bami bukuwe - my me-ness is in you.

The Makhandzambili (Forerunners) project is quite fractal, because it's in the School of Commons, but the aim of it is to produce a School of Commons. We're trying to create a similar space, but one that is brought in from perhaps a different tradition, in the same spirit.

Ubuyena bomuntu buvela kithi ngenxa yokuthi sixoxe ngaye - the them-ness of a person arises in us as we converse together.

We want online spaces, because they make broad access possible. But we also want in-the-flesh engagements: to be present in a physical space together. We want both, and we want all, because we are both and all.

Zonke izinto zivela enxoxweni - everything arises from the conversation.

A multimodal space is potentially a fertile peer learning space; though right now it requires a lot of technical infrastructure… but it's going to require less and less effort to set up virtual reality spaces in the future.

Ukuthiwa ngukusho. Umuntu ngumusho. - To be said is to intend. A person is an intent.

We were thinking carefully about the space that we want for such an environment, and an ideal space presented itself in the person of a cave.

Into ekhona yilena enobuwena. Into engekho inobumina kuphela qha. - That which is present is that which has you-ness. That which is absent is that which only has me-ness.

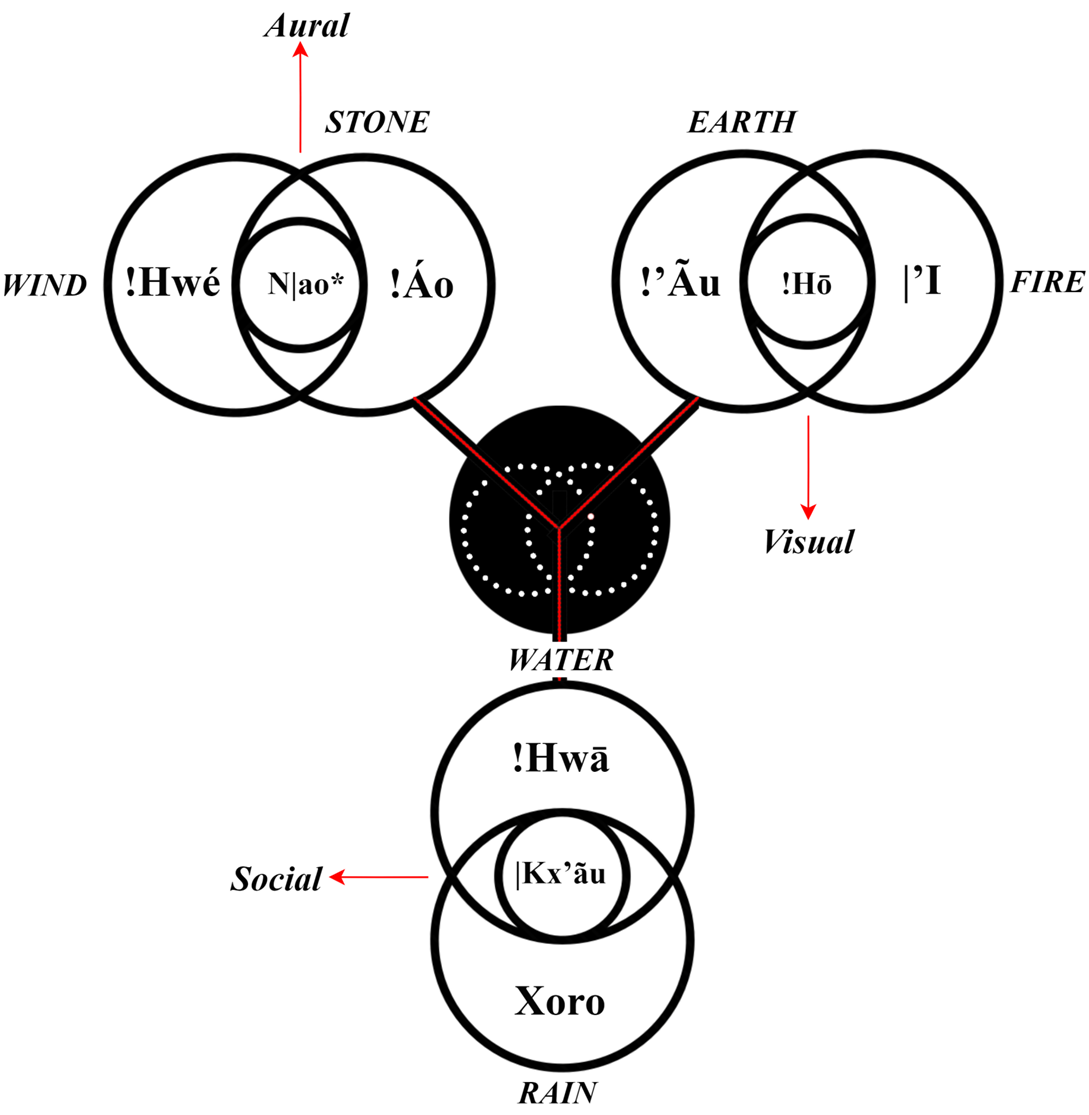

We engaged three caves: a sound cave, a visual cave, and an exchange cave. That is the structure that we work on, coming from the structure of the cosmogony in the |Xam tradition of Southern Africa.

Uqobo lomuntu ngubuwena bakho. Mina ngiyimi oyimi ngawe. - The reality of another is your you-ness. I am me who is me (only) by you.

My workshop, when we had the School of Commons event last year, expressed these narratives as an interpretive tool. The whole project also hinges that cosmogony of local source, and that is creating a decentralised global space of ideas together.

Umuntu ngumuntu onguye ngathi. - A person is that person that is them (only) through (our) us.

Kit: A big part of this project is a multi-modal VR component. What sparked that?

Pule: VR is kind of fundamental in the conception, it's not an extra feature. In previous experience with SodaWorld Studios, there was an important realisation of this idea of “Decentralising Home”: home for us being there in Johannesburg, with people engaging with that space globally. Johannesburg inner city, does come with the infrastructures, and the violence that all built environments have around the world, but especially so in such a settler colonial space that was largely driven by the gold rush. It was a gold rush town and it's remained in that ethos since 1886. Until now, it has this idea that people are there to make the riches; it's a hustler’s place, and so all the infrastructure is towards a business-centered mentality in the city. It has a lot of energy in there, as a lot of like inner city places within cultures across the world, even like in the USA; we have all these cultural movements that come from inner city life, in a context that is obviously fraught and violent. Now we thought, okay, so how do we start a new space of real peer learning, of non hierarchical collaboration in the clear ethos of the thing?

It's not just a global space, it's highly rooted in a physical environment that has its own complex history, and its own complex positionality, and that richness of that is more than you could imagine and create. You know, real life is often much more wild and entertaining than fiction: you can only imagine so much, there's going to be much more richness in real life, rooted in a lived space with history. When you put that in a digital space, it releases much more of an interactive energy - there's much more possibilities. That was the first insight into the importance of VR as a medium: it is a way of getting engagement from around the world in a very localised, but decentralised way. This is part of what we refined with the SodaWorld space through a number of hybrid events where the participation is in the flesh, and virtual, in the 3D [VR] world, which is a digital twin of the physical space. There's also various chat streams, and people who are just joining, facilitating multiple modalities of engagement. Being aware of multiple perspectives at the same time is a very good training for us to start to become dexterous in managing multiple perspectives at once, in real time, you know?

The Sidvwaba Cave is the oldest known cave in the world. It’s six kilometers into the mountain, and it has this huge cavernous dolomite amphitheatre inside. It has incredible acoustics because its dolomite rock absorbs the sound. There is a feature called “Somcuba’s Gong” which is a lithophone that you hit with a rubber hammer - the rock resonates when you strike that, and it's not an echo in the cave, because there's no echoes; it's the rock itself that resonates. The cave has been a venue over the years for many music performances, such as the likes of Miriam Makeba. Imagine the kind of history of the performances that are happening in the space, and the space itself being so old, and being felt as a completely new, natural environment: literally grounding because it's the ground, and also a neutral space - it’s full of a potential of something completely new to happen in that space. It doesn't come with these histories of a built environment - the infrastructure and the industry - that produces a space; it's something that has been there for millions of years and predates any kind of industry. This natural environment is ideal, as the ground for collaboration and learning to happen. The gravitas of this ancient, enormous natural space, gives you that rarefied context of learning. This space is so old that nobody has a real claim to it, so the idea is to see it as itself, and to engage with it, you know, as an elder, as it were, and as a collaborator herself, this stone (ǃÁo in the |Xam cosmogony). VR also creates the potential to engage that space without actually being inside it physically, while communing virtually inside it.

Kit: I'm interested in what you think about the unseen observer, or the passive participant, because I think, especially in the darkened aural space of the cave, on a physical level, you can stand there, and you can be very quiet and silent, and you cannot necessarily be perceived by others. And then that can be a very direct analogue of online participation sometimes.

Pule: You know, the last time I was at the cave, a couple of weeks ago, I was there for three days. On the last day, I actually spent some time just sitting in the cave. There wasn't much happening, there were two groups going through, so I was sitting in amphitheatre space in the dark. And I was sitting in that space for a while, as you say, being in the dark, and I was trying to also record sound, because I wanted to have a little ambient sound of the space in the different chambers, like in the very large chamber, very small one, walking, the sound of water dripping with water dripping in the cave. I'm sitting there in this amphitheater in the dark, and when the tour comes through, I don't want to be seen, but inevitably the tour guide is very observant, or is looking around the space - they see a shadow in the darkness, they say, “Who's that?” And then they look, and then they recognise me. As an unknown figure, especially when somebody is a tour guide that’s supposed to be responsible… I'm sort of aware that I might be causing a little bit of anxiety by being just a passive occupant of the darkness in the space. But I desperately want to just do that at that moment, and it's a wonderful thing to be able to do that. Then the person realises, okay, it's a benign figure, I'm just chilling there, then they just carry on.

The passing moment of a crescendo of presence, is a very interesting way of understanding what happened. At some point, someone is going to see that you're on a zoom, and you don't put your camera on, you don't say anything, and there's a lot of people on the zoom. At some point, someone's going to see that, and there's going to be a crescendo of presence. Managing that is an interesting moment; there is a difference between that peak in awareness of presence, and in the wash of silent presence where it's not acknowledged, and no one's thinking about this. I think that's a very interesting dynamic to play with. It's also got a lot of potential in there, especially because it’s something that sets a lot of Schools of Common spaces apart: if you don't want to participate, you don't have to. That's a very important feature of it. Building in the interesting and non threatening moments of crescendo of presence into an experience with others is a very good thing to be conscious of and to practice. Because just as I wanted to be alone in the dark in the cave at that moment, and I was slightly anxious that this person is going to be anxious, a mutual anxiety about each other's presence, and then there's the moment of that relation, and that catharsis of the realisation that everything’s just carrying on - I think that's one very nice experience that I had, that I could foresee would happen in all sorts of modalities - the tension of the interaction and the release.

We people are experiencing what has been created digitally, but we have to work out the ways of making it a digitally livable space; a space where people are coming there for this function of literally listening to each other, and listening to the space. I would love for all the School of Commons alumns and everyone that was interested to be involved in this idea of an aural-centered space of collaboration.

SoC Alumn Update: Mutual Aid and Local Events. In the past few months, the alumn coordinator, Kit (SoC ‘22), has gotten input from recent SoC alumns on how to best use the SoC alumn resources. This newsletter is a big part of that; it will highlight the ongoing work of SoC alumns. Additionally, this network can be used for mutual aid requests on a case by case basis.

These occasional alumn updates will continue to feature ongoing projects, and any upcoming events advertised mostly through social media. The focus this year will be on in-person or hybrid local alumn events. If you’re a School of Commons alumn and interested in hosting an event with SoC support; offering your ideas or feedback; contributing an interview; or getting in touch about a featured project - please reach out by replying!

Writing about particular peer learning projects, I feel that Elisa’s comment about classical music in the Listenings rings true more broadly: “It's about classical music, but it's also about attention and concentration on something that is abstract, but we all share it. It's in the room, but we don't see it. It develops in time, but we don't see it.” The subject matter is vital, and so is the shared attention and concentration that develops in our shared time(s) and space(s).

With love & until next time,

Kit Kuksenok

All images courtesy of the contributing artists: photo from Elisa Lemma, and diagrams from Pule kaJanolintji.